Suddenly the San Diego middle schooler was sleeping all day and awake all night. When in-person classes resumed, she was so anxious at times that she begged to come home early, telling the nurse her stomach hurt.

Whitney tried to keep her daughter in class. But the teen’s desperate bids to get out of school escalated. Ultimately, she was hospitalized in a psychiatric ward, failed “pretty much everything” at school and was diagnosed with depression and ADHD.

As she started high school this fall, she was deemed eligible for special education services, because her disorders interfered with her ability to learn, but school officials said it was a close call. It was hard to know how much her symptoms were chronic or the result of mental health issues brought on by the pandemic, they said.

Schools contending with soaring student mental health needs and other challenges have been struggling to determine just how much the pandemic is to blame. Are the challenges the sign of a disability that will impair a student’s learning long term, or something more temporary?

It all adds to the desperation of parents trying to figure out how best to help their children. If a child doesn’t qualify for special education, where should parents go for help?

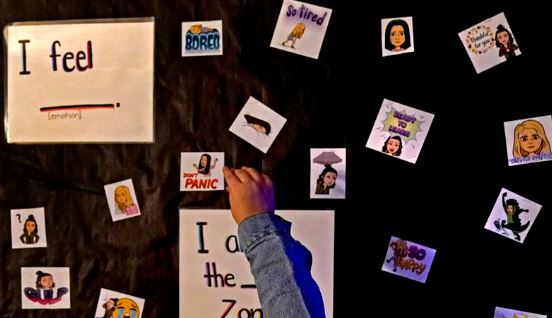

“I feel like because she went through the pandemic and she didn’t experience the normal junior high, the normal middle school experience, she developed the anxiety, the deep depression and she didn’t learn. She didn’t learn how to become a social kid,” Whitney said. “Everything got turned on its head.”

Schools are required to spell out how they will meet the needs of students with disabilities in Individualized Education Programs, and the demand for screening is high. Some schools have struggled to catch up with assessments that were delayed in the early days of the pandemic. For many, the task is also complicated by shortages of psychologists.